A boy in Brooklyn, NY, killed a gay black man, and the world thinks I will keep going about my workday.

I want to talk about the murder of O'Shae Sibley with my people, but there is nowhere to go. There is no third space to hold us, to discuss our contradictions or grief in a way that won't stop time. I want to build a fort with my people to ask all the hard questions, cry and plan for the future we can't rely on. But instead, I am on a facilitation call asking seven other black queer organizers I know if we are seeing/feeling the same thing.

I scroll past another IG story with an emoji next to an image of Sibley, and the words RIP is repeated across my phone screen as I struggle to find decent wifi at a coffee shop in Center City, Philadelphia. The coffee shop is cash only, all windows with neutral salmon-colored walls. I am the only black person in the store that morning, and I can feel it.

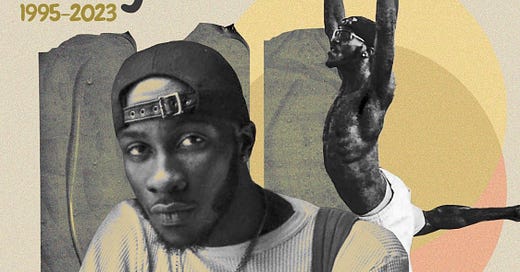

Sibley, originally from Philadelphia, moved to Brooklyn in 2020 to chase his dreams of being a full-time dancer and became a member of the House of Old Navy and the House of D'Mure-Versailles.

So I sit in that coffee shop to be with Sibley's dance legacy and the grief of his people that will reverberate in ways many of us will never know. Taking time to mourn or sit with the questions about what solidarity looks like or means to those most at risk means stopping time. It means sitting with the precarity of black queer life when the world wants me to believe I should be happy enough that I wasn't the one killed this time around.

The world/internet/domination makes moral living hard; it takes away our choices to live in right relationship and makes virtue signaling about our righteousness more important than how we act in the real world.

I started to contemplate in that sterile coffee shop about Beyonce's Renaissance, the safety of a world/tour built by the greatest artist of our time, and how even that could not keep Sibley safe. That the hollow promise of visibility is, in fact, about being seen without any guarantee of care or afterthought; as ballroom culture and black queer people reach more heights in the public sphere, the gap in actual safety seems to grow wider as the systems of harm remain intact, as the trick mirror of visibility keeps us looking in the wrong direction.

Renaissance in keeping the legacies of Moi Renee alive, in rendering Kevin Aviance and Kevin JZ Prodigy speechless seeing their innovation finally cited in real time plays in tandem with the reality that cis men are killing our people. The systems we live in contradiction with, which are corrosive to our well-being and the safety of the people we say we love, still beat every day. Sadly, I don't know how we stop the grim thing from breathing.

When I was in college, I dated a boy who lived in Brazeal Hall; as I grew older, I learned that in 2002, Aaron Price assaulted a student named Gregory Love with a baseball bat in Brazeal Hall at Morehouse College. The case became Georgia's first hate crime after passing the Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2001. I had been in the bathroom of Brazeal Hall many times, in love and unaware of the legacy of violence under my feet. Love survived the attack, and Price served ten years of prison time for the homophobic assault. That case and the near erasure of it from Morehouse's history feel like a distant calling to Sibley's attack. If we knew what happened where we stood would we hold our folks tighter than the day before?

I wonder who was walking Essex Hemphill home after his writing group sessions or who was caking on the phone with June Jordan when she followed Fannie Lou Hammer around Mississippi while writing a children's book. I don't want to explain to white people, straight people, or anyone who lives on top of me why they should make sure their little brother doesn't kill a gay black man over the weekend. I want to get under a blanket with my people and plan on how we all make it home alive.

Please stay tuned for my upcoming series, Black Ppl Run The Internet dropping on ChaoticGood this week